Introduction to the "field" concept and the modelling thereof

The above statement is a good illustration of the difference between Mathematics and Physics. In Physics, Mathematics is a fantastic tool. It allows us to make highly accurate predictions and formal descriptions of the processes we observe to take place in Nature. In a way, Mathematics is a very powerful language, because the symbols it uses and defines, have an enormous expressive power. Perhaps, above all, it is this expressive power, formalized in a language, which makes it so very useful in Physics.

It is this same expressive power, for example, which makes Python such a powerful programming language. One of the reasons Python is such an expressive programming language is because in a way "everything goes anywhere". You can add "strings" and "numbers" in Python, for example, which is a bit like adding apples and oranges in other languages. The disadvantage of such a language, however, is that sometimes errors occur when a program is being run with unexpected inputs.

The same argument can be made about Mathematics. Mathematics doesn't care if you are trying to multiply apples and oranges, even though the obtained result has no meaning in the "real world". So, what makes Mathematics such a powerful tool and language, is that because it defines all kinds of abstract concepts, relationships and calculation methods in a formal symbolic language, it has an enormous expressiveness. Expressiveness, which can be used to accurately describe all kinds of processes and systems and to solve all kinds of problems associated with these. However, it does not give a "real world" meaning to these abstract concepts it studies and describes.

So, it is not up to Mathematicians, but up to Physicists and Engineers to make sure that the Mathematics they use actually produce meaningful results. This is illustrated by Albert Einstein, who wrote in "The Evolution of Physics" (1938) (co-written with Leopold Infeld):

As we saw earlier, Freeman Dyson illustrated how Maxwell´s field model, which was founded upon well described and understood Newtonian principles, gradually evolved from a meaningful concept into a pure abstract concept, whereby eventually all connection to the "real world" has been lost:

In his paper "A Foundation for the Unification of Physics"(1996) Paul Stowe described this as follows:

Currently, the field concept has departed so much from Maxwell's down to Earth origins, that there is little room left to distinguish the modern field concept from pseudo-science, if we are to follow Karl Popper's definition:

With the current definitions of, for example, the electric-, magnetic- and gravitational fields, there are both units of measurement as well as instruments with which one can measure the strength of these fields. In hindsight, we might argue that these units of measurements are defined somewhat arbitrarily, but they are measurable nonetheless and thus "make possible the comparison with experiment".

But what about "virtual particles", "dark matter", "weak nuclear forces", "strong nuclear forces" and even "10 to 26-dimensional string theories"? Isn't there a strong sceptic argument to be made here that, at the very least, these kinds of unmeasurable concepts are bordering on the edge of pseudo-science?

Either way, even though we are well aware of the wave-particle duality principle and should have concluded that therefore there can be only One fundamental force and therefore only one field, a plethora of fields have been defined, none of which has brought us any closer to the secret of the "old one." So, if there can be only one fundamental physical field of force, what is it's Nature? How do we use this wonderful Mathematical and abstract concept of a "field" and use it in a physically meaningful way?

Let us simply go back to something that stood the test of time: the original foundation Maxwell's equations were based upon, which is to postulate the existence of a real, physical fluid-like medium wherein the same kind of flows, waves, and vortex phenomena occur as which we observe to occur in, for example, the air and waters all around us. We shall do just that and then work out the math, using nothing but "classic" Newtonian physics, meanwhile making sure that the mathematical concepts we use have a precisely defined physical meaning and produces results with well defined units of measurement.

And since it is the field concept which has made a life of it's own, let us first consider what we mean by a physical field of force and define it's units of measurement, so that we can clearly distinguish a physical field of force from the more general mathematical abstract field concept we use to describe our physical field. That way, we can do all kinds of meaningful calculations, predictions and experimental verifications. And just like 2*6=12 has no meaning in and of itself in Physics, the abstract mathematical field concept has no meaning in and of itself in Physics. To sum this up:

In a way, Physics is the art of using abstract Mathematical concepts in a way that is meaningful for describing and predicting the Physical phenomena we observe in Nature.

In practice, that comes down to a book-keeping exercise. All we really need to to is to keep track of which mathematical concept we use to describe what. For example, if we use the abstract field concept to describe something we call a physical field of force, we should unambiguously associate a unit of measurement to the abstract mathematical concept used. This way, we have clearly defined what the abstract concept means within a certain context. In Software Engineering, this is what's called type checking:

Just read "unit of measurement" for "type" and we are talking about the exact same concept.

Introduction to vector calculus and fields of force

While this statement by Albert Einstein may or may not ring true to you, many people will ask the question: "What does it mean?" Since it is precisely that question that concerns us when we want to define what we mean by a "physical field of force", let us consider this statement a little bit further, because we will be using partial differential equations to describe our model, although we will make use of the expressiveness vector calculus offers us in order to keep things understandable and to express the concepts we are considering in a meaningful way.

As an illustration of the expressive power of vector calculus, let us consider the definition of "divergence":

{$$ \operatorname{div}\,\mathbf{F} = \nabla\cdot\mathbf{F} = \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial}{\partial y}, \frac{\partial}{\partial z} \right) \cdot (U,V,W) = \frac{\partial U}{\partial x} +\frac{\partial V}{\partial y} +\frac{\partial W}{\partial z}. $$}

At the left, we have the notation in words, followed by a notation using the $\nabla$ operator ($\nabla$ is the Greek letter "nabla"), while at the right, we have the same concept expressed in partial differential notation. So, when we use this $\nabla$ operator in equations, we are actually using partial differential equations. However, with the notation we will use, we can concentrate on the physical meaning of the equations rather than to distract and confuse ourselves with the trivial details.

So, what Einstein actually said was something like that the concepts we will use, too, gradually morphed from being useful and meaningful tools into essentially taking all branches of physics hostage. As early as 1931, Einstein already recognised that it was no longer reasoning and fundamental ideas that guided scientific progress, but rather a number of abstract concepts which drifted ever further away from having any physical meaning at all, a destructive process which still continues this very day and age.

Now let us briefly introduce the main mathematical concepts we will use: divergence, curl, gradient, some "identities" and the Laplace operator:

As an intuitive explanation, one can say that the divergence describes something like the rate at which a gas, fluid or solid "thing" is expanding or contracting. When we have expansion, we have an out-going flow, while with contraction we have an inward flow. As an analogy, consider blowing up a balloon. When you blow it up, it expands and thus we have a positive divergence. When you leave air out, it contracts and thus we have a negative divergence.

It can be both denoted as "{$ div $}" and by using the "nabla operator" as "{$ \nabla \cdot $}".

In fluid dynamics, divergence is a measurement of compression. And therefore, by definition, for an incompressible medium or vector field, the divergence is zero, like for example with the magnetic field, which is called Gauss's law for magnetism:

{$$ \nabla \cdot \mathbf{B} = 0 $$}

curl:

[...]

[...]

Let us note that, unlike the divergence, the curl as both a length and a direction, which means that it gives you a vector, while the gradient gives you a single number, which is called a scalar.

The gradient concept is very similar to that of Grade or slope:

Intuitively, the gradient gives you the direction and size of the biggest change of a function. In the mountain analogy, the gradient points in the direction a ball put on a mountain surface would start rolling. The steeper the surface, the bigger the gradient.

Let us note, that unlike the divergence which takes a vector and gives you a scalar value, the gradient takes a scalar and gives you a vector. So, the gradient and the divergence are complementary to one another.

physical field of force:

The three concepts just introduced (divergence, gradient and curl), are what is mathematically called derivatives:

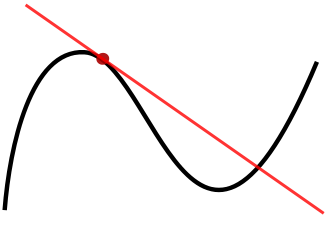

When working in 1 dimension, the derivative is intuitively very similar to the gradient concept, as can be seen from this WikiPedia picture, which also illustrates the mountain analogy used to describe the gradient:

So, the mathematical concept of derivative says something about the "thing" it's the derivative of. In 1 dimension, 1D, this is always the rate of change of the function the derivative is calculated of.

Now this concept can be applied multiple times. For example, like the derivative of the position of a vehicle gives it's speed, the derivative thereof on it's turn gives you the rate of change of speed, which is called "acceleration". And since it's the second derivative of position, it's called the second derivative, or the second order derivative:

{$$ \mathbf{a} = \frac{d\mathbf{v}}{dt} = \frac{d^2\boldsymbol{x}}{dt^2}, $$}

Now let us consider Newton's second law of motion:

{$$ \mathbf{F_N} = \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{p}}{\mathrm{d}t} = \frac{\mathrm{d}(m\mathbf v)}{\mathrm{d}t} $$}

{$$ \mathbf{F_N} = m\,\frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{v}}{\mathrm{d}t} = m\mathbf{a}, $$}

From this, we can make an intuitive, first explanation for what a physical field of force actually is:

A physical field of force is the 3D version of the 1D concept of acceleration.